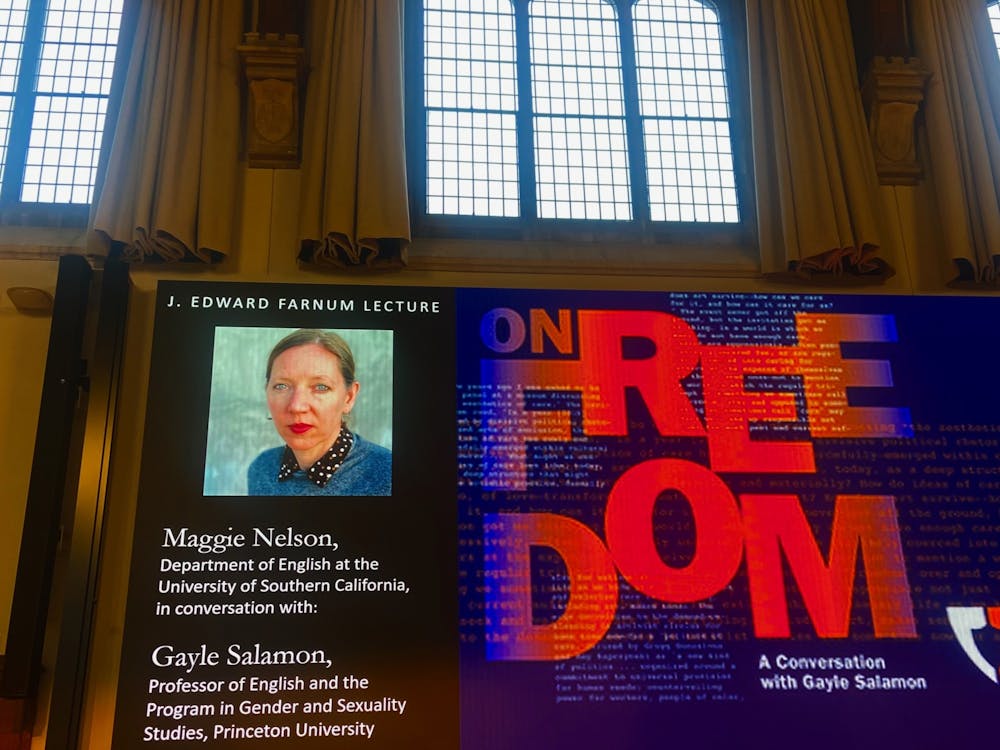

On Thursday, April 7, writer, poet, and professor Maggie Nelson joined Princeton Professor of English and the Program in Gender and Sexuality Studies Gayle Salamon on the McCosh 50 stage for a public lecture on her newest book, “On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint.”

In a recent review, The New York Times labeled Nelson’s most recent project an exploration of the paradoxes of freedom. Divided into four sections — art, sexual freedom, drugs and addiction, and the climate crisis — the book, as Nelson explained in her lecture, discusses how freedom is a topic we are unable to quit, perhaps because we are never exactly sure what we are talking about. This is a beautiful characteristic of much of Nelson’s work: she lounges in uncertainty, unafraid of loose strings or unanswered questions whether that be in her texts on motherhood, queerness, or even the color blue. Freedom, then, in all of its ambiguity and import, seemed like a natural topic for Nelson to tackle next.

In her conversation with Salamon, Nelson drew upon French philosopher Michel Foucault’s definition of freedom. To Foucault, Nelson explained, freedom is a practice — an act that takes up most of our day. Together, Nelson and Foucault imagine a world in which freedom exists separately from obligation — in their view, the concept should be unfurled, a slow experimentation that can take place even in the mundane or everyday.

Nelson reclined in an armchair atop the McCosh 50 stage as she mused on the topic of freedom. She spoke quietly and slowly, sitting with the uncertainty of unanswered questions, yet each phrase burning with intentionality. Despite my second-row seat, I was required to lean forward to catch every word.

Still, I found myself desperate for the answers to come faster and louder. It’s possible this desire was tinged with a feeling of obligation — I spent much of the pandemic in Nelson’s world, scrupulously annotating both “The Argonauts” and “Bluets,” two of her earlier works. I felt close to her. It was a closeness enabled by shared texts — the most wonderful type.

Paradoxically, “The Argonauts” particularly served as a bit of a lighthouse as I struggled to assimilate my own queerness; in many ways, I needed answers and Nelson refused to give them. She writes, early on in the text, “To align oneself with the real while intimating that others are at play, approximate, or in imitation can feel good. But any fixed claim on realness, especially when it is tied to an identity, also has a finger in psychosis.” And again, “A becoming in which one never becomes, a becoming whose rule is neither evolution nor asymptote but a certain turning, a certain turning inward, turning into my own / turning on in / to my own self.”

Much like her writings, and even Nelson herself, I learned to accept my queerness through uncertainty — to turn inwards, to experience a becoming in which one never really becomes. Unanswered questions and refusal of labels were okay in the world of “The Argonauts” — encouraged even. Nelson’s texts allowed me to find comfort in the irresolution of my sexual identity.

There, sitting in the enormous lecture hall, I reflected on the power literature has to help us understand ourselves. Or, in Nelson’s case, to understand that we may never understand ourselves. The conversation between Nelson and Salamon was wonderful, though I’ve admittedly only just begun to read “On Freedom” — it was as if I had walked in on two old friends catching up. Again, Nelson’s words on ambiguity and uncertainty, even when talking about freedom, comforted me.

As the conversation came to an end, though, Salamon asked Nelson about a quotation from philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein that she included in one of her earlier books: “If you are unwilling to know what you are, your writing is deceit.”

Quotations from philosophers and academics well outside of my range of knowledge dotted the conversation between Nelson and Salamon, but this one stood out to me — mostly because it seemed incongruent with Nelson’s previous musings on irresolution to which I so often found myself clinging. Is this what I had been doing while lounging in my own uncertainty? While unable to label my sexuality? Was I unwilling to know myself?

It’s an important question, and one I want to continue to consider. But Nelson’s answer — slow and quiet and deliberate, above all — aided me in this consideration. To instances when her writing could be figured as a certain refusal to know herself, she responded with this: “That’s as much as I was permitted to know at the time.”

There’s much to be said, here, about half-formed concepts of selfhood. Nelson’s answer, as her thoughts so often do, comforted me. She seemed to be suggesting that the development of the self, as well as the process of understanding our own varied identities, is exactly that: a process, dynamic and changing and uncertain.

In many ways, this, in my limited experience, is college: half-formed, pieced-together identities, attempting to present as a whole. It seems like we are faced with opportunities to define ourselves, once and for all, every day — in class choices, majors, friend groups, and extracurriculars.

Just the other day, walking through the center of campus, I stumbled upon a horde of sophomores on Cannon Green posing in front of orange and black banners reading “MATH,” “COMP LIT,” and “CHEMISTRY.” It was Declaration Day, and finally, after months of deliberation, adding and dropping classes, and frantic meetings with advisors, sophomores could find some certainty.

Nelson’s words rang in my ears as I passed by: “That’s as much as I was permitted to know at the time.” Perhaps these eager students would switch majors, add certificates, or even completely change career paths. Perhaps they would make these changes tomorrow, or in 12 months. Either way, Nelson’s words remind us that in all of our uncertainty, clarity can emerge. They remind us that our current understanding — or confusion — of ourselves, right now, is enough. It is enough to have gaps in conceptions of identity. And it is enough to write and read and learn and choose and drop majors and exist until we are permitted to know more.

Clara McWeeny is a Staff Writer for The Prospect at the ‘Prince.’ She can be reached at claramcweeny@princeton.edu, or on social media @claramcweeny.

Self essays at The Prospect give our writers and guest contributors the opportunity to share their perspectives. This essay reflects the views and lived experiences of the author. If you would like to submit a Self essay, contact us at prospect@dailyprincetonian.com.